The Provençal Life of Mary Magdalene

According to the Huis Bergh Missal

In 1475, the St. Mary Magdalene Guild of an unnamed church in the city of Bruges, Flanders collected alms to commission the production of a missal to be used in celebration of the Mass. This was to be no ordinary Roman missal of prayers, hymns, text, and the liturgy for the feast days, but one whose decoration was centered on and worthy of their patron Saint Mary Magdalene to whom they were devoted. It was to be the ultimate tribute to Mary Magdalene’s importance to the Christian faith and the strong tradition of celebrated legends that had circulated about her for centuries and retold in the Golden Legend.

The work of illuminating the missal is thought to have been given to the master illuminator Willem Vrelant and probably painstakingly produced by one of his apprentices at his workshop. It was completed in 1476, according the inscription page that also lists the patrons and Guild Masters of the Church who commissioned it. The missal is now known as the Huis Bergh Missal, after having been acquired by the Huis Bergh Foundation.

Whereas most missals include only one full-page of miniature illuminations, this one contains two, both with elaborate border decoration. The missal also includes 18 historiated initials, numerous images in the margin, painted initials on all pages and penwork initials on some. The two folios with elaborate decoration and pictorial miniatures of Mary Magdalene’s life in Provence are depictions of legends seemingly directly drawn from the folklore and legends contained in the medieval bestseller Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend).

As the centerpiece of the two folios is a miniature illumination of Mary Magdalene inside a royal temple canopy holding a prayer book, symbolizing her devotion to her faith. In her other hand, is her most common identifier, the alabaster jar, containing the costly anointing spikenard that, according to the Gospels, she used to anoint Jesus’ head (or feet) at the house of Simon the Leper. The background places her temple in Marseilles as evidenced by the quaint 15th century Provencal architectural features of the buildings. There is a fairytale-like charming quality to the backdrop.

Along the borders, the legends of Mary Magdalene’s life according to the Golden Legend come to life. It resembles a storyboard of the legends associated with her exile and apostolic mission in Provence and Rome.

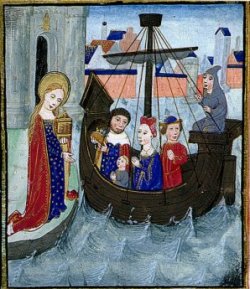

Arrival in Marseilles

Fig. 1 Mary Magdalene arrives in Marseilles in a boat with no rudder.

The Christian tradition that tells of the arrival of Mary Magdalene and her companions on the coast of Gaul (France) goes back to the earliest centuries of Christianity and has numerous versions. In about 1260, some of her legends and other hagiographies of the Saints, were compiled by Jacobus da Varagine, titled Legenda Aurea, and later made available to medieval readers. By the 1500’s more copies were printed and in circulation than the Bible.

According to the Golden Legend,

“S. Maximin, Mary Magdalene, and Lazarus her brother, Martha her sister, Marcelle, chamberer of Martha, and S. Cedony who was born blind, and after enlumined of our Lord; all these together, and many other Christian men were taken of the miscreants and put in a ship in the sea, without any tackle or rudder, for to be drowned.”

As told, it was through the grace of God that they were carried across the Mediterranean and deposited safely on the shores of Marseilles.

Another version of the Christian legend lists the passengers of this miraculous voyage as Martha, Lazarus, Mary Salome and Mary Jacoby, the disciples Maximin and Sidonius (two of the 70 disciples referred to in the Gospels), along with Marcella their servant.

An old canteque, a song of Provencal tradition whose age is unknown, provides an alternative list that includes other notable passengers, including Joseph of Arimathea. One verse is as follows:

Entrez, Sara, dans la nacelle

Lazare, Martheet, Maximim,

Cleon, Trophime, Saturninus

Les trios Maries et Marcelle

Eutrope et Martial, Sidonie avec Joseph

Vous perirez dans le nef.

The Sara mentioned first in the list, accompanied by the three Maries, Martha, Lazarus, Torphimus, Maximin, Cleon, Eutropius, Sidonius, Martial, Saturninus and Joseph of Arimathea, was afforded her own legend as a saint in the Golden Legend and is still celebrated by gypsy pilgrims in an annual festival with grand processions in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, a village 128 km from Marseilles. According to legend, the exile party embarked from Alexandria, Egypt to begin a new chapter in Gaul, first landing on the shore of Sainte-Maries-de-la-Mer. Sara was described as a dark-skinned Egyptian handmade to the Maries. In recent years, some authors such as Margaret Starbird have even suggested that this Sara was actually the daughter of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, a theory that rings true for many who believe Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married.

The year of the exile party’s arrival in Gaul was 36 AD, but the Church puts the date at 42 AD to correspond with the martyrdom of James the Just, the brother of Jesus.

The illuminator seems to have portrayed yet another version of this legend, perhaps one lost to the record or one created out of the illuminator’s mythic imagination and artistic license. In the boat, are four male saints and a handmaiden to see to Mary Magdalene’s needs during the journey. Perhaps, the illuminator chose this portrayal, omitting the other Maries and Martha as to not overshadow Mary Magdalene’s import. One is left to wonder.

The

Apostolic Mission in Provence and Rome

Fig. 2 & 3 Mary

Magdalene Evangelizing in Provence

According to tradition, the exile party began to preach near the temples of the gods of the various pagan traditions in Massilia (Marseilles) at the time. Greeks, Romans, and Phoenicians, as well as the more native Ligurian Celts all had settlements in Massilia at the time and their own pagan deities, gods and goddesses, that they worshipped and celebrated with a calendar full of festivals. Jewish settlements were also amongst them, made up of those forced out of Palestine and granted a charter of liberty by the Romans. It was a diverse culture under Roman occupation and the Romans were tolerant the various religions.

The Church’s propaganda teaches that Mary Magdalene and her companions denounced “false” (pagan) gods, and spread the Good News, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. They were said to have been responsible for converting many in these communities and therefore credited with bringing Christianity to Gaul.

In time, Martha leaves the group to go to Tarascon, a place approximately 25 miles northwest of Massilia; Maximin goes to Aix, 20 miles north of Massilia, while Mary Magdalene, Lazarus and Sidonius continue to preach in the city of Massilia.

Born out of these legends, churches, some housing relics, were erected and continue to be centers for pilgrimage by those seeking spiritual renewal. The ninth-century church of Holy Maries in the Camargue, the church of St. Maximin that enshrines a body claimed to be that of Mary Magdalene, the cave of Sainte Baume where it’s said Mary resided in hermitage for some 30 years, the cathedral at Arles commemorating St. Throphinmus, the Church of St. Martha at Tarascon and the fourth century Abbey of St. Victor at Marseilles, a memorial to St. Lazarus, are all sites imbued with the rich history of these first evangelists to the region.

Born out of these legends, churches, some housing relics, were erected and continue to be centers for pilgrimage by those seeking spiritual renewal. The ninth-century church of Holy Maries in the Camargue, the church of St. Maximin that enshrines a body claimed to be that of Mary Magdalene, the cave of Sainte Baume where it’s said Mary resided in hermitage for some 30 years, the cathedral at Arles commemorating St. Throphinmus, the Church of St. Martha at Tarascon and the fourth century Abbey of St. Victor at Marseilles, a memorial to St. Lazarus, are all sites imbued with the rich history of these first evangelists to the region.

Fig. 4 Mary Magdalene in Rome

There is no mention of Mary Magdalene evangelizing or traveling to Rome in the Golden Legend. Therefore, the storyboard of the missal strayed from its primary source and included another legend popular at the time.

The earliest mention of the claim that Mary Magdalene went to Rome is in the Gospel of Nicodemus (Acts of Pilate) which was written in the Fourth century and which, like the Golden Legend, became popular reading during the Middle Ages, explaining why the illuminator added a Rome visit to his storyboard. The gospel is an apocryphal gospel, claimed to have been derived from an original Hebrew work written by Nicodemus, who appears in the Gospel of John as an associate of Jesus. But its legitimacy as historically valid is questionable if not farfetched.

The reference mentioning Mary Magdalene’s plans to travel to Rome reads as follows:

"...Mary Magdalene said, weeping: Hear, O peoples, tribes, and tongues, and learn to what death the lawless Jews have delivered him who did them ten thousand good deeds. Hear, and be astonished. Who will let these things be heard by all the world? I shall go alone to Rome, to the Cæsar. I shall show him what evil Pilate has done..." (Acts of Pilate Chapter 11)

The Eastern Orthodox tradition also claims Mary Magdalene traveled to Rome, where she challenged the Emperor Tiberius to accept her story of Jesus’ resurrection with the same amount of pious fervor as Nicodemus’ telling. Most are familiar with the Red Egg Legend in which Mary Magdalene holds up an egg that turns red with her announcement, signifying Christ had risen. It became a tradition in the Eastern Orthodox churches. Eastern Orthodoxy holds that Mary Magdalene was “Apostle to the Apostles” and claim her relics were moved to Constantinople from Ephesus where she died.

There is an even more interesting reference to a Mary having evangelized in Rome that is more historical than legend, although it is not clear who this Mary was. It is found in Romans 16:6. According to Paul, this Mary was the most prominent member of a group of both men and women who traveled to Rome and laid the groundwork in establishing the Church in Rome. Richard Fellows comments on this notable "Mary" in his blog article titled Paul and Coworkers .

The question arises: Was this Mary who deserved respect as a leader of the Church Mary Magdalene?

The Worker of Miracles

Fig. 5 Legend: Mary Magdalene Helping the Prince and his

Lady to Conceive

A very popular legend thought to have originated in the 10th century and one included in the Golden Legend is the miraculous conversion of the Prince of Marseilles and his Lady. It is retold in the miniature storyboard in the Huis Bergh Missal with four miniature illuminations. Unless one was familiar with the story, the illustrations would be impossible to interpret.

The legend tells that the Prince and his Lady (wife) were desperate to conceive a child. They were visited by Mary Magdalene in visions on three separate occasions, first to the wife and then to the Prince. Mary chastises them for participating in pagan sacrifices and berates them for their greedy lifestyle and neglect of the poor.

After Mary preaches to them about Jesus Christ, the couple becomes increasing convinced by her sermon and put Mary and her God to the test:

“To whom (Mary Magdalene) then the prince said: I and my wife be ready to obey thee in all things, if thou mayst get of thy god whom thou preachest, that we might have a child. And then Mary Magdalene said that it should not be left, and then prayed unto our Lord that he would vouchsafe of his grace to give to them a son. And our Lord heard her prayers, and the lady conceived. ….”

The Prince, wanting to verify what Mary Magdalene had preached about Jesus Christ, plans a voyage to Rome to ask St. Peter. While on the voyage, the Prince’s wife succumbs to a prolonged and violent labor and dies giving birth to a son.

Fig. 6 Prince’s

Wife and Infant in a Death Slumber

“And when the child was born he cried for to have comfort of the teats of his mother, and made a piteous noise. Alas! what sorrow was this to the father, to have a son born which was the cause of the death of his mother, and he might not live, for there was none to nourish him….Then covered he the body all about with the mantle, and the child also, and then returned to the ship, and held forth his journey.”

Fig. 7 Prince

Meets with St. Peter in Rome

The story continues,

“And when he came to S. Peter, S. Peter came against him, and when he saw the sign of the cross upon his shoulder, he demanded him what he was, and wherefore he came, and he told to him all by order. To whom Peter said: Peace be to thee, thou art welcome, and hast believed good counsel. And be thou not heavy if thy wife sleep, and the little child rest with her, for our Lord is almighty for to give to whom he will, and to take away that he hath given, and to reestablish and give again that he hath taken, and to turn all heaviness and weeping into joy.”

Peter then takes the Prince on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to visit all the places Jesus had performed his miracles, preached and where he was crucified. Once the Prince was well informed on the faith and two years passed, he departed for his own country. They sailed by the rock where the body of his wife and son were left. The Prince then marvels at what he witnesses:

Fig. 8 Two Years

Pass and Prince Returns

“And the little child, whom Mary Magdalene had kept, went oft sithes to the seaside, and, like small children, took small stones and threw them into the sea. And when they came they saw the little child playing with stones on the seaside, as he was wont to do. And then they marvelled much what he was.”

The jubilant Prince then pleas for the resurrection of his wife. His request answered with a miracle comparable to the raising of Lazarus.

“O blessed Mary Magdalene, I were well happy and blessed if my wife were now alive, and might live, and come again with me into my country. I know verily and believe that thou who hast given to me my son, and hast fed and kept him two years in this rock, mayst well re-establish his mother to her first health. And with these words the woman respired, and took life, and said, like as she had been waked of her sleep: O blessed Mary Magdalene thou art of great merit and glorious, for in the pains of my deliverance thou wert my midwife, and in all my necessities thou hast accomplished to me the service of a chamberer. “

The final scene finds the Prince and his wife back in Marseilles to witness Mary Magdalene with her disciples preaching. The couple then accepts the baptism of St. Maximin.

This fable is filled with implausible marvels and portrays Mary Magdalene as savior and mediator between the divine (Christ) and humans facing disappointment, hardship and misfortune. She holds the power to turn minds toward the heart and towards accepting a new faith in a God that as William Granger Ryan, translator of the Golden Legend, explains defines God "not a philosophical abstraction but a living, ever-present, caring actor, the creator and giver of life."

Mary Magdalene’s

Hermitage in St. Baume

Fig. 9 Mary

Magdalene in her Grotto in St. Baume

This historiated initial is a snapshot of one of the most popular legends associated with Mary Magdalene in Provence—Mary Magdalene’s thirty-year hermitage of repentance in a grotto cave in St. Baume. Tradition says that after some months of evangelizing, Mary Magdalene and the disciple Sidonius leave Lazarus behind in Massilia, where he takes his seat as the first bishop, and travel northward, following the Huveaune river until they reach the hills that would become known as La Sainte Baume. They discover a natural cave in the rocks and Mary Magdalene settles in to begin her long hermitage. Some miles down the valley was the Roman village of Villalata that would later be renamed Saint-Maximin-La-Sainte-Baume.

The St. Baume legend tells that after 30 years of hermitage the day came when Jesus announced to her that death was approaching. He guided her down the hill towards the village of Villalata. On the way there, she was greeted by Maximin and led to his church. There she received holy communion from his hand and collapses before the altar. The date was July 22 (her feast day) around the year 72 A.D.

However, according Golden Legend it was into the desert that Mary wandered, a version that appears conflated with the legend about another Mary—Mary of Egypt.

The Golden Legend reads:

“…after when she (Mary Magdalene) came into the country of Aix, she went into desert, and dwelt there thirty years without knowing of any man or woman. And he saith that, every day at the seven hours canonical she was lifted in the air of the angels. But he saith that, when the priest came to her, he found her enclosed in her cell; and she required of him a vestment, and he delivered to her one, which she clothed and covered her with. And she went with him to the church and received the communion, and then made her prayers with joined hands, and rested in peace.”

Fig. 10 Mary

Rises Flanked by Angels as Queen of the Heavens

The Gnostic

Mary Magdalene

Fig. 11 Mary Magdalene

as Apostle to the Apostles

Although iconography during this period sometimes depicts the Virgin as a central figure amongst the Apostles to support the Mariology of the Church, there were those who venerated Mary Magdalene as the “Apostle to the Apostles”, as depicted here. Mary Magdalene’s divinity is represented by the dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, and she is portrayed in a similar light as Christ, perhaps even so far as to say she was Christ’s divine complement, feminine counterpart and successor, and therefore afforded similar spiritual power. In fact, the hand gesture Mary Magdalene uses (Fig.4 and Fig.5) in which the first two fingers and thumb are extended is one reserved for Christ in the iconography in Christian art. It emerged as a sign of benediction (or blessing) in early Christian and Byzantine art, and its use continued through the Medieval period, and into the Renaissance. It signified Christ’s power to bless and to heal and became a gesture of a priestly function for the male-only papacy. The fact Mary Magdalene, a woman, is portrayed as a practicing Christian priestess and afforded equal power to Christ would certainly not fall within the theological parameters of the Church. No woman could assume such a role to date. But there was an underground stream of Christianity, a Gnostic Mary Magdalene tradition that viewed her as the embodiment of feminine aspect of God and worshipped her with as much commitment and intensity as the Orthodox Church worshipped Christ.

This particular miniature represents one of several clues suggesting the illuminator was a member of or at the very least familiar with the beliefs of this underground stream of Gnostic Christianity that venerated Mary Magdalene as Sophia, the personification of the Wisdom aspect of God. A second clue is that the book Mary Magdalene holds in the miniature under the temple canopy (Fig.1) has an “X” (oblique cross) imprinted on the cover. The “X” was emblematic for the Gnostic Mary Magdalene tradition and represented a signature for a mystery called Bridal Chamber, a mystery described in the Gospel of Philip, a gnostic apocryphal text from the 3rd century.

In Conclusion

What is most unusual about the series of miniatures in the Huis Bergh Missal about the life of Mary Magdalene is that it omits the common depictions of the Gospel narratives relating to Mary Magdalene’s role as myrrh bearer, her position at the cross, arrival at the empty tomb and as the first witness to the resurrection. It instead puts its emphasis on her own ministry and role in bringing Christianity to Gaul. She is viewed as leading an exemplar Christian life, more fierce and faithful than penitent, converting communities, creating miracles of healing, having her own disciples, and preaching on an Apostolic mission in Provence and Rome. Jesus seems to take a back seat in the decoration of this missal, with only a handful of miniatures and historiated letters relating to his Christology, such as a crucifixion scene in the first pages. The Virgin seems to have been afforded even less attention.

What is most unusual about the series of miniatures in the Huis Bergh Missal about the life of Mary Magdalene is that it omits the common depictions of the Gospel narratives relating to Mary Magdalene’s role as myrrh bearer, her position at the cross, arrival at the empty tomb and as the first witness to the resurrection. It instead puts its emphasis on her own ministry and role in bringing Christianity to Gaul. She is viewed as leading an exemplar Christian life, more fierce and faithful than penitent, converting communities, creating miracles of healing, having her own disciples, and preaching on an Apostolic mission in Provence and Rome. Jesus seems to take a back seat in the decoration of this missal, with only a handful of miniatures and historiated letters relating to his Christology, such as a crucifixion scene in the first pages. The Virgin seems to have been afforded even less attention.

One might wonder what the Mass and sermon would have sounded like at this particular church or chapel on Mary Magdalene’s Feast Day. During the Middle Ages there was no single complete or correct text for the missal. While the Canon of the Mass was the same everywhere, each province and in some cases individual diocese had their own variations on the texts used for the feast days and could have different saints honored, often because of regional significance to them. In this case, the guild from the Bruges community drew from the legends of Provence, specifically those compiled in the Golden Legend, to celebrate their most beloved Saint Mary Magdalene. It is the only missal of its kind.

As a preacher and a composer of sermons, Jacobus probably intended his Golden Legend to be a source book for preachers. And the Huis Bergh Missal suggests the legends were used in celebration of the Mass as he intended. The modern usage of legend as "an unhistorical traditional story" emerged only after 1600. Therefore, for the medievalists in Bruges and throughout France these legends were embraced as fact more often than fiction.

_____________________

Images from Collection Dr. J. H. van Heek, Huis Bergh Foundation, Images © The Huis Bergh Foundation, CC BY 4.0.

References

Benbassa, Esther, The Jews of France: A History from Antiquity to the Present, Translated from the French by M. B, Princeton University Press, 1999. http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s6706.html

Green, Ariadne, Jesus Mary Joseph: The Secret Legacy of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, Palm Leaf Press, 2012

Rudy, Kathryn M, How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts, Open Book Publishers, 2016

Starbird, Margaret. Mary Magdalene, Bride in Exile. New Mexico: Bear and Co., 2005.

The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints

Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275 First Edition Published 1470

English by William Caxton, First Edition 1483

Volume 4

From the Temple Classics Edited by F.S. Ellis. First issue of this Edition, 1900 Reprinted 1922, 1931

Links:

Tillotson, Dianne, Medieval Writings - Missals http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/word/missal.htm

Tide book "Calendar and word Missalis fratrum minorum segundum consuetudinem" handwriting on parchment commissioned by Jooris Weilaert and Jacop van Craylo, 1475 -1476, Brugge

http://www.collectiegelderland.nl/organisaties/huisbergh/voorwerp-0285

Video of Huis Bergh Missiel, Art Collectino Castle Huis Bergh, Netherlands, produced by Musick Monument.

https://youtu.be/23Unk3dUVhg

Copyright Ariadne Green 2017

References

Benbassa, Esther, The Jews of France: A History from Antiquity to the Present, Translated from the French by M. B, Princeton University Press, 1999. http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s6706.html

Green, Ariadne, Jesus Mary Joseph: The Secret Legacy of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, Palm Leaf Press, 2012

Rudy, Kathryn M, How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts, Open Book Publishers, 2016

Starbird, Margaret. Mary Magdalene, Bride in Exile. New Mexico: Bear and Co., 2005.

The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints

Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275 First Edition Published 1470

English by William Caxton, First Edition 1483

Volume 4

From the Temple Classics Edited by F.S. Ellis. First issue of this Edition, 1900 Reprinted 1922, 1931

Links:

Tillotson, Dianne, Medieval Writings - Missals http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/word/missal.htm

Tide book "Calendar and word Missalis fratrum minorum segundum consuetudinem" handwriting on parchment commissioned by Jooris Weilaert and Jacop van Craylo, 1475 -1476, Brugge

http://www.collectiegelderland.nl/organisaties/huisbergh/voorwerp-0285

Video of Huis Bergh Missiel, Art Collectino Castle Huis Bergh, Netherlands, produced by Musick Monument.

https://youtu.be/23Unk3dUVhg

Copyright Ariadne Green 2017